I'd been in

Abkhazia for a week and I was getting bored. I'd come looking for an adventure

but instead I had been seduced by the warm waters of the Black Sea and the

excellent Abkhaz wine which I had been drinking liberally since I'd arrived.

I'd always liked the idea of a traditional beach holiday, set in beautiful

surroundings but with the backdrop of a war zone.

The juxtaposition of leisure and horror intrigued me. However as I

had soon realised after crossing the Ingur bridge into Abkhazia, this small country

only lived up to half of the bargain. It was stunning, a naturalist’s paradise

but the terror was over, I could sleep safely. And whilst that was a good thing

for the local population who had witnessed enough horror, selfishly, I was a

little disappointed.

I was in the southern town of Ochamchire, a town

that privileged Soviets had flocked to in great numbers before the fall to

relax on its pebble beach and soak up the southern sun. But the days of

Ochamchire's beaches being full of holidaying apparatchiks and their families

were but a distant memory. Now the town was a sleepy backwater that had few

visitors and a wrecked tourist infrastructure. An abandoned hotel stood at one

end of the beach and looked out over a beautiful shore line that now had more

cows strolling along it then holidaymakers.

Ochamchire is a town where every

street is a reminder to the war and the ethnic cleansing that took place there.

As the victorious Abkhaz fighters backed by the Russian army pushed the

Georgian army out across the Ingur river back into Georgia the ethnic Georgian

population who had lived in Abkhazia for generations followed them carrying

what they could and leaving what they could not. They were the lucky ones. The

stragglers and the brave were rounded up and herded into Ochamchire's football

stadium from where women and children were systematically raped and the men

were killed. Streets of empty houses the only reminder to their presence in the

country and the genocide committed against them. I'd asked people in

the town how they felt about the fact that the neighbours that they had grown

up with sharing their vines and wells had been allowed to be so cruelly

treated. Was there a sense of common shame? Few were willing to utter more than

a few words on the matter. History may well be written by the victors but they

seem less inclined to speak.

My map showed a solitary road heading deep into

the Caucus mountains beginning in Ochamchire and ending at the town

of Tkvarcheli, in the mountains some 30 kilometers away. With no idea as

to what I would find there but with no better options I flagged down a passing

taxi. A battered Volga pulled up driven by a silver haired Abkhazian man. Levar, as he introduced himself, was confused by my request. "Why don't I take you

to Novi Afon instead, the scenery there is more beautiful." He was

reluctant to take me to Tkvarcheli insisting I'd not like the place. I

increased my offer to 1500 Roubles, a foolishly high sum for such a short

journey and reluctantly he asked me to get in. We left Ochamchire, passing

through streets and neighbourhoods where nine tenths of the houses were

abandoned and burnt out, the Georgian quarter. As we drove on into the

foothills of the Caucus mountains the more suspicious Levar became of my intentions

there. "What do you want to go to Tkvarcheli for?" he pressed. I'd

already explained that I just wanted to have a wander around, I was bored of

the beach, but that raised his suspicions further, "They will think you

are a spy and arrest you," he said looking at me without a hint of humour.

"Well then they'll shoot you for collaborating with the

enemy," I said teasing. We drove on in silence.

As the road climbed out of the foothills and

into the mountains the temperature dropped. We drove into a patch of fog but

when we appeared through the other side we did so into a landscape of verdant

hills, rushing mountain streams and the occasional abandoned building. It was a

stunningly beautiful place. It was also more Soviet then the coast, the

signposts, the hammer and sickle motifs on buildings, there had not been such a

rush to eradicate the reminders to the past. It was also noticeably

poorer. Abkhazian people had been wonderfully friendly on my trip. This

trip to the Caucuses, my first, had been an epiphany for me. For years I had

associated the Russian language and all who spoke it with an unsmiling solemnness.

But here in the Caucuses for the first time I saw the Russian language used by

races who used the language as an instrument to convey happiness. People smiled

at strangers, they said dobri-den whilst passing on the street. It was nothing

short of shocking to walk into a shop to be welcomed by smiling faces speaking

Russian (Russian is the lingua franca of Abkhazia and the Caucus region) and

not to be made to feel as though you were a nuisance. Yet here in the mountains

on the road to Tkvarcheli there were no smiles. As we passed half abandoned

villages people watched us pass, but seemingly with suspicion etched on their

faces. It seemed outsiders didn't come this way much. The road was empty

without any other vehicles on it save the occasional army truck loaded with

Russian conscripts. I'd heard nothing but resentment towards the Russian

military presence in Abkhazia. Shortly after crossing the border into Abkhazia

a week earlier the marshrutka I had been travelling in had been stopped at an

army road block manned by Russian soldiers. All the passengers and I were

ordered outside for a documentation inspection. The Abkhazian passengers were

seething that they were being stopped and inspected by Russians in their own

country. It was plain to see where the real power lay in Abkhazia and the

locals resented it.

We drove on in silence and passed a sign

announcing our entry into the Tkvarcheli region, Lavar the driver turned to me

and reminded me that I should be careful. Rounding a corner the view of

Tkvarcheli opened up in front of us. It was not a pretty sight. In a mist

shrouded valley lay the lower half of the town, the industrial area, the coal

mine, the now abandoned railway station, some disused factories with

their decaying towers and some Stalinist buildings long abandoned and beyond

repair. And up higher on the upper slopes of the mountain side lay the centre

of the town, the worker's quarters and all that was necessary for life.

Stretched out high above the town and linking both halves, the upper and the

lower, were steel cables holding a couple of now disused cable cars, stranded

midway between the wheel houses, no doubt used to transfer the workers from the

upper half of the town down to the mine. It was a scene unlike any I had ever

seen on my FSU travels before. An ugly town, run down and decaying but

paradoxically set in such lush and beautiful surroundings.

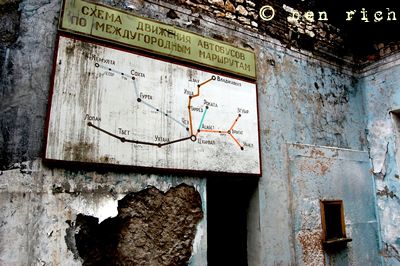

I asked Levar to park up by the railway station

that stood at the entrance to the lower half of the town. I switched on my

camera, "Don't let anybody see you," Levar instructed tetchily. I

entered the collapsing terminal building built in the classical style Soviet

architects of the early period were instructed to build. It had not been used

for years but once had train services to Sukhumi and beyond. I walked along the

overgrown platform, nobody in sight, the lower half of the town was dead. As I

walked to the end I saw Levar hiding behind a wall watching me. Did he suspect

me of being a spy or was he just looking out for me? In Ochamchire I had been

complacent about being in a conflict area, but up here in Tkvarcheli with Levar

and his warnings about me being arrested or being seen things felt different. A

strange feeling was growing inside me, one I did not recognise. We returned to

the car, Levar wanted to return to Ochamchire but I insisted we drive on.

We passed derelict factory buildings until

coming to a traffic circle which marked the entrance to the upper part of the

town. It was surrounded on three sides by Stalinist apartment buildings,

solidly built but long abandoned. The street was empty except for two guys

loading a large sack into the back of a Lada. They stopped and eyed us suspiciously

before dumping the sack in the trunk of the car and driving off. We parked up

next to a fast flowing river and I got out. "If you see someone hide your

camera and act normal," Lavar instructed. I ran across the open space in

the centre of the road and into an over grown and disused park which

had a dilapidated fountain and beyond that a shell of an apartment building.

It

was rare to see housing of such quality in the former Soviet Union. These

buildings were built with quality materials and built to last. They had not

collapsed, but had been stripped of their wood. Window frames, roof lintels,

floor joists. They'd been needed perhaps in the cold winter months of the war.

I'd seen plenty of Krushevkas in states of disrepair but these were different, this

was not worker's housing. I walked through the park following the cracked

cement pathway. It was deserted, the only sound being that of the river running

through the centre of town. I returned to the car.

We crossed the river and

climbed higher into the upper town. There was no sign of modernity, nothing to

suggest we were in the new millennium. The streets were empty except for

the occasional Soviet built car and glum looking pedestrian who stood and

watched as we drove past. There were a few shops built into the bottom of

Stalinist apartment buildings which had painted wooden signs advertising what

they stocked 'Shoes', 'Products', 'Bread'. It was like a film set. We pulled up

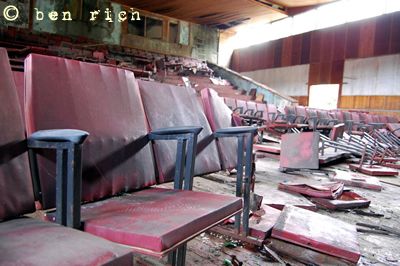

at an abandoned theatre, outside were some workmen taking a rest from painting

a building on the opposite side of the road. I entered the theatre through a

broken door in the lobby whilst undoing my zip, better they think I was

urinating on their theatre then photographing it. Its rooms had the detritus of

the towns past cultural life; a rotting cupboard of costumes, discarded

celluloid film reels, a ballet shoe hanging on a nail.

The auditorium was a jumble of rotting leather chairs. How had it

come to this? Was the squalor in the town the result of the war, or the result

of a collapsing economy that was no longer spoon fed on subsidies?

We drove on

passing more glum pedestrians shuffling along semi deserted streets. At the

time of the last great Soviet census in 1989 the population of the town stood

at 22,000. Twenty years on it is less than 5000. People had left the town at

the first opportunity. Why? Levar turned to me as we drove, "Who are

you?" he asked, my previous explanation that I was just a tourist had

obviously not convinced him. "Really, who are you?" I'd never had

that question put to me before and for a moment I was unsure as to what he

meant, but what he meant was what was I doing up here in the mountains of

Abkhazia in some hell hole photographing everything that everybody else ceased

caring about 20 years ago? It was a good question, one I had no real answer to,

but in his mind he knew the answer. I either really was a spy or more likely,

an idiot. People wanted to escape this town yet I'd sought it out despite his

best efforts to steer me away. Why was I not in Novy Afon with the other

tourists?

Everything in the town was so imposing, hewn

from grey rock, built to survive the winters. During

the independence war in the early 90's Georgian forces had besieged

Tkvarcheli and tried starving the town into submission. The town's population

had held out for over 400 days until Abkhaz forces with Russian help had

relieved the town. It was a town built to endure, physically and mentally. We

took another road that led to a plateau high above the town and came to an

abandoned restaurant overlooking a bend in the river. It was a beautiful

setting; the town planners had chosen their spot well. The restaurant was built

on a raised plinth with a glass front that opened up the view to the distant

snow-capped mountains, up here with nobody watching Levar relaxed a little. He

went to the trunk of his car and pulled out a bottle of sickly sweet Abkhaz

wine and a dirty plastic mug. "This place was a fine restaurant, you

needed connections to get a table. I heard Beria ate here". We both sat in

silence and drank the sickly sweet wine gazing out at the view. Talk of Beria

and the images that his name conjured up brought back the feelings of unease

I'd felt since entering this town. As we finished the last of the wine Levar

asked if I wanted to see anything else but I'd seen enough and did not like

what I had seen.

I'd visited run down towns all over the former

Soviet Union in search of reminders of the near past but this place was

different. The difference was that in other towns and cities there had been

small reminders to the past in a sea of steadily growing modernity, a krushevka

building surrounded by glass office buildings, a crumbling Soviet bus stop

mural plastered with posters for an Ace of Base concert, an abandoned fishing

boat. They were subtle reminders of the late Soviet period. There were of

course two Soviet Unions: Pre-Stalin's death and post. Post-1953 was Yuri

Gagarin and Sputnik, it was Glasnost and the Moscow Olympics, it was Alla

Pugachova pop songs and Tarkovsky films, it was Kvass dispensers and

Cheburashka cartoons. It was a familiar place that on the surface at least was

not too different to our own countries. I could have found a place for myself

in that world. Tkvarcheli was not of that world. Tkvarcheli was built in the

early 1940's,a nastier more vicious period. And it did not just offer a glimpse

into that time; it seemingly still inhabited it.

The abandoned apartment

buildings on the traffic circle overlooking the only road into the town were

too well built to have been built for the workers; instead they were built for

the nomenclature of the Stalinist period: party cadres and their

families, securitat men, directors of the factories. And nobody achieved those

positions in those dark days without having blood on their hands, without

handing over a list of names, without reporting to someone. Nobody got to

live in the well-built apartment overlooking the park in Tkvarcheli unless they

were able to mute the voice of their conscience and do

certain despicable things. Up there looking out of their apartment

windows they would have seen all who came and went into the town, making mental

notes. The coal mine, the life blood of the town would have been mined by the

hands of prisoners, people torn from their homes and dumped here. Nobody would

have come to this damp valley unless it was through force or instruction. The

town was built to supply coal to the Soviet industrial machine; quotas would

have to be filled with dire consequences for ones that were not met. And how

did those prisoners arrive in the town? They walked along the very platform I'd

walked on at the railway station earlier. The abandoned restaurant I was

sitting in had not been not for the town's folk to enjoy but for the ruling

elite and that meant people implicit in crimes. The cold stares, the paranoia,

the constant watching as we drove past – it was too real. I'd always wondered

how it would have been to have lived in the Soviet Union in the height of Stalin's paranoiac reign

where nobody was to be trusted, where you were watched and spied upon by your

closest neighbours and family. Where there were certain buildings you dared not

walk past because of the horrors contained within. Now for the first time in my

travels I felt the faint touch of its tentacles, the first sting of fear and

despair. Tkvarcheli was a cruel place, sodomised by its own collusion with

history. Lavar sensed it and had tried to warn me without verbalising the fact.

And now I had come to sense it too. Tkvarcheli was a concrete testament of

man's inhumanity to man.

We drove back from the restaurant along the half

deserted streets passing the more Stalinist buildings. A man in a suit ran out

of a building towards us shouting in a language I did not know, Levar

accelerated past him. I watched him in the wing mirror as he pointed at our car

whilst frantically shouting at a passersby. I turned to look at Levar for an

explanation but he was staring ahead,jaw tensed in the direction of the road

out of town. I was glad to be heading there with him.

Fantastic narrative.

ReplyDeleteThrough memory we travel against time, through forgetfulness we follow its course.

ReplyDeleteFlights to kinshasa

Cheap Flights to kinshasa

Cheap Air Tickets to kinshasa

Finding flights is a mammoth task however have you ever wondered how the airlines decide which price to charge you? this article shows exactly how the airline industry operates and could also save you hundreds on your flight tickets no matter where or when you are traveling.

ReplyDeleteair charter

Fascinating journey! So what did you finally answer to your guide's "who are you?" Questions?

ReplyDeleteNice info.. thanks for sharing .

ReplyDeletemyanmar tourism

a light view form past places

ReplyDeleteairport parking gatwick

Gatwick airport parking