Kurban Ait 2008 in Cholpon Ata and Kochkor, Kyrgyzstan

Written by Nicola

To see the complete set of photographs from Kurban Ait 2008 CLICK HERE.

Kurban Ait (Eid al-Adha), the Muslim festival of sacrifice, is celebrated across the Islamic world with prayers and gifts of food and money to the poor. In the spirit of the time of piety, Ben, D., and I decided to take our 3-day weekend and visit Kyrgyzstan’s premier beach resort.

Cholpon Ata truly deserves the title of Central Asian beach paradise. For a start, the shores of Lake Issyk-Kul are the only place for about 3000 miles where you’re likely to encounter a beach. The golden, sandy shoreline and inviting warm waters (“issyk” means “hot” in Kyrgyz, so it must be, right?) entice sun worshippers in their hundreds from as far afield as Bishkek, Almaty, and even Tokmok city. In the height of the summer season, the small town of Cholpon Ata, on the lake’s north shore, transforms into the Speedos capital of the world.

Not that much of this was evident when we visited in November 2008. The streets were deserted; the guesthouses and Soviet-era sanatoria boarded up and closed. Driving into town in our taxi, we asked the driver to take us somewhere to stay. Every door that he knocked at was opened by hard-faced babushkas who moved us on with barely an apologetic shake of the head. We pulled into the vast, crumbling remains of what must have once been one of the premier sanatoria retreats of the Soviet Union. Here, beds were to be had, at the rate of several hundred US dollars a night, and no doubt cheap at the price to experience this piece of history. Regretfully aware that our budgets were too tight to allow such opulence, we asked the driver to once again try elsewhere. Around this time, clearly aware that we weren’t going to find anywhere, he very kindly offered to let us stay in his house, at much more the going rate for a Kyrgyz homestay, to which we readily agreed.

Once settled into the homestay, after the obligatory tea-drinking, admiring the orchard in the courtyard (nothing much to look at in November) and playing with our host’s fat but friendly cat, we headed out to see the sights of Cholpon Ata. First up was lake Issyk-Kul itself. The “jewel of the Tian Shan”, its Kyrgyzstan’s number one tourist draw, at least according to the locals. It dominated the town, glittering blue in the late autumn sunlight. We searched in vain for a way to get down to it, through a park sporting a huge silver statue of a woman being attacked by birds, and a solitary cow; on through the back streets of what in summer must be a beachfront promenade; past burning piles of refuse. Finally, we found a militsya (an officer of Kyrgyzstan’s military police – the police’s crack bribe-demanding unit). D. asked him in Russian for directions to the beach, which he smilingly provided. Grateful, and somewhat amazed at our still-intact wallets, we headed out onto the golden sands, here and there dotted with discarded vodka bottles and crumbling concrete ruins. Atop one of these concrete structures, maybe once a beachfront kiosk we posed for photos, looking out over lake and beach to the towering, snow-clad mountains. Another concrete wall provided stylish graffiti of Lenin and Stalin. Further down the coast, we could see the much more modern concrete hulks of the private villas where Kyrgyzstan’s elite would come to while away their summers.

Written by Nicola

To see the complete set of photographs from Kurban Ait 2008 CLICK HERE.

Kurban Ait (Eid al-Adha), the Muslim festival of sacrifice, is celebrated across the Islamic world with prayers and gifts of food and money to the poor. In the spirit of the time of piety, Ben, D., and I decided to take our 3-day weekend and visit Kyrgyzstan’s premier beach resort.

Cholpon Ata truly deserves the title of Central Asian beach paradise. For a start, the shores of Lake Issyk-Kul are the only place for about 3000 miles where you’re likely to encounter a beach. The golden, sandy shoreline and inviting warm waters (“issyk” means “hot” in Kyrgyz, so it must be, right?) entice sun worshippers in their hundreds from as far afield as Bishkek, Almaty, and even Tokmok city. In the height of the summer season, the small town of Cholpon Ata, on the lake’s north shore, transforms into the Speedos capital of the world.

Not that much of this was evident when we visited in November 2008. The streets were deserted; the guesthouses and Soviet-era sanatoria boarded up and closed. Driving into town in our taxi, we asked the driver to take us somewhere to stay. Every door that he knocked at was opened by hard-faced babushkas who moved us on with barely an apologetic shake of the head. We pulled into the vast, crumbling remains of what must have once been one of the premier sanatoria retreats of the Soviet Union. Here, beds were to be had, at the rate of several hundred US dollars a night, and no doubt cheap at the price to experience this piece of history. Regretfully aware that our budgets were too tight to allow such opulence, we asked the driver to once again try elsewhere. Around this time, clearly aware that we weren’t going to find anywhere, he very kindly offered to let us stay in his house, at much more the going rate for a Kyrgyz homestay, to which we readily agreed.

Once settled into the homestay, after the obligatory tea-drinking, admiring the orchard in the courtyard (nothing much to look at in November) and playing with our host’s fat but friendly cat, we headed out to see the sights of Cholpon Ata. First up was lake Issyk-Kul itself. The “jewel of the Tian Shan”, its Kyrgyzstan’s number one tourist draw, at least according to the locals. It dominated the town, glittering blue in the late autumn sunlight. We searched in vain for a way to get down to it, through a park sporting a huge silver statue of a woman being attacked by birds, and a solitary cow; on through the back streets of what in summer must be a beachfront promenade; past burning piles of refuse. Finally, we found a militsya (an officer of Kyrgyzstan’s military police – the police’s crack bribe-demanding unit). D. asked him in Russian for directions to the beach, which he smilingly provided. Grateful, and somewhat amazed at our still-intact wallets, we headed out onto the golden sands, here and there dotted with discarded vodka bottles and crumbling concrete ruins. Atop one of these concrete structures, maybe once a beachfront kiosk we posed for photos, looking out over lake and beach to the towering, snow-clad mountains. Another concrete wall provided stylish graffiti of Lenin and Stalin. Further down the coast, we could see the much more modern concrete hulks of the private villas where Kyrgyzstan’s elite would come to while away their summers.

Wandering back into town, we paused to admire the smattering of propaganda billboards lining the main drag. “сила народа в единстве” (power of the people is in unity) announced a huge picture of (since-deposed megalomaniac) President Bakiyev, stern in front of lake and mountains. Further along the street, a smiling woman urged us to invest in the kind of gated community which just doesn’t exist in Kyrgyzstan, and which, due to some poor Photoshop skills, appeared to on the verge of being submerged by a tidal wave. But my personal favourite cannot really be done justice in words. Emblazoned with the slogan “коррупцияга жол жок” (corruption is not the way), perhaps its effect explains us escaping a shakedown.

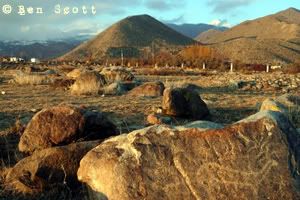

Our next destination was a site virtually unknown to the Kyrgyz and Kazakh tourists who yearly flock to Cholpon Ata. A little out of town, past a cemetery, lies a boulder-strewn field. Unassuming to the casual observer, the field may even seem off-limits due to the huge ditch and concrete markers which cut it off from the town. Clamber over the ditch, however, and wonders await the careful (and patient) observer. Petroglyphs, remnants of ancient Sogdian and Turkic peoples, are carved seeming at random into the rocks. Deer, goats and camels, even a hunting scene with dogs, artistically rendered by enigmatic peoples now long gone. One of the builders working on the ditch had decided that in front of this last scene was the perfect place for to relieve himself.

As we descended from the petroglyph field, sunset painted the surrounding mountains impossible shades of pink and gold, while evening mist over Issyk-Kul seemed to solidify into yet more peaks. Shepherds on horseback drove their cattle down through the boulders to their camp. The ornate tombs in the cemetery stood stark against a fiery sky. The temperature dropped as rapidly as the light, and it was a relief to huddle into a small cafe (seeming the only one open in town). Removing our heavy winter coats, we ordered dumpling soup, and sat shivering until it finally dawned on us that the interior of the cafe wasn’t heated, and was therefore no warmer than the sub-zero temperatures outside. I’m not sure if their represents social conditioning, or merely a distinct lack of common sense on our part. Finishing our dumplings, we headed back through the now pitch black night to our homestay, warmth, and the obese cat.

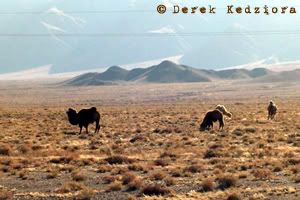

The next morning, we were up early and hoping to secure transport to the village of Kochkor in central Kyrgyzstan. Cholpon Ata and Kochkor both being renowned urban centres (hah), this may well have taken all day. Luckily for us, we were able to engage a taxi driver to take us without having to wait for another passenger to fill the car. Thanking our host, we set off, and were soon belting through the rolling Kyrgyz countryside on a comparatively good road (it even had tarmac). Speeding around a corner just north of the brilliant blue Orto-Tokoy reservoir, an unexpected sight filled the windscreen. Shouting at our driver to stop (which he did, grinning at the strange behaviour of foreigners), we began snapping pictures of a small herd of Bactrian (two-humped) camels grazing peacefully beside the road, miles from the nearest human settlement, and a very rare sight in Kyrgyzstan.

By this time, one of the pitfalls of living in Central Asia was beginning to make itself known to D., who was suffering from a bout of giardia, so we hurried on toward our destination. We arrived at the office of Community Based Tourism (CBT) in Kochkor, and through them were able to arrange a homestay for the night and a horse riding trip for the next day. We also spent some time perusing and purchasing shyrdaks (traditional Kyrgyz felt rugs) from the attached shop belonging to a local women’s collective. Afterwards, we took a walk around the village, taking in local highlights including a gaudy, silver statue of Lenin on a mosaic plinth, a bubbling spring rising from the ground in the local rubbish dump, and children playing among the rust-and-tetanus-riddled remains of what may once have been a shipping crate. Streets lined with Soviet-era decorations depicting motifs of rockets, hammer and sickles and atomic nuclei provided a counterpoint to the imposing mountain backdrop, viable over the high walls of family compounds lining the unpaved streets. Back at the homestay, we were plied with food and drink almost to bursting by the incredibly mothering proprietress, who made sure that we were comfortable with extra blankets and heaters, Soviet-era tourist literature to peruse, and even going as far as to tuck me in for the night.

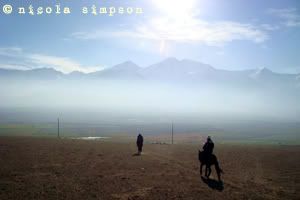

The following day was Kurban Ait itself. After a huge Kyrgyz-style breakfast consisting of fermented yoghurt, borsok (fried squares of dough), and copious quantities of amazing homemade jam, we met our guide for the day and saddled up for a day’s horse riding.

Nothing beats the freedom of galloping through the vast landscapes of Central Asia, through cragged mountains and broad meadows where flocks of fat-bottomed sheep graze and golden eagles wheel high above. Each twist in the trail seems to bring you closer to the country. In the grounds of the mosque, the imam and his attendants were slaughtering sheep and goats as part of the festival. Dogs in scattered farms barked as we rode by. Further on, another beautiful, eerie cemetery appeared out of swirling mist, ethereal domes topped with crescent moons recalling Arabian Nights adventure and orientalist mystique. Streams, frozen solid in the harsh mountain climate, made playgrounds for children sliding on homemade sleds.

Arriving back in Kochkor, we returned to our homestay to collect our shyrdaks. Our hostess welcomed us in, and sat at the table, where steaming plates piled high with plov (an Uzbek dish made of rice, carrots and mutton) were pressed on us. A man joined us, one of the festival celebrants, going from house to house spreading good wishes. He ate with us, recited a prayer and wished us good health. Our hostess refused to accept any payment for the meal; during Kurban Ait, food is provided for all visitors, even foreigners smelling of horse!

Sadly, we said our goodbyes, and loaded down with our bundles of felt purchases, we bundled ourselves into the back of a taxi heading for Bishkek. The return journey was largely unremarkable – we chatted about inconsequential things, and at one point were almost involved in a head-on collision with a truck, at which nobody in the taxi batted an eyelid until a few minutes later D. asked “Did we just almost die?” In testament to how long we had collectively spent in Central Asia, this didn’t seem cause for concern. Back in Bishkek, with my shyrdak spread across my bedroom floor, and the horse smell dissipated by a hot shower, I prepared for another working week in the metropolis.

To see the complete set of photographs from Kurban Ait 2008 CLICK HERE

very very nice post and very interesting!! I enjoyed also in Kochkor. There I felt the hospitality of the kyrgyz people.

ReplyDeleteThank you for share!!